We again are happy to partner with Sojourners in publishing this article by our editor:

Socialism is more popular in the U.S. now than at any time since the early 20th century, and religion played a big part in both eras. Just like socialists today rally around Bernie Sanders, who credits his Jewish heritage for shaping his beliefs, the 1900s movement was led by Eugene Debs, who was deeply influenced by Christian socialists of the time.

Consider that, while serving his prison sentence for speaking against the military draft of World War I, Eugene Debs hung a single picture on the wall of his cell: the pain-wracked visage of the crucified Jesus Christ with a crown of thorns. To the clergy assigned to visit him, Debs explained the affinity.

“He denounced the profiteers, and it was for this that they nailed his quivering body to the cross,” he said. “If Christ could go the cross for his principles, surely I can go to prison for mine.”

A few years earlier, in a characteristically unsubtle essay entitled “Jesus the Supreme Leader,” Debs made a more detailed case for Christ as the ultimate socialist agitator.

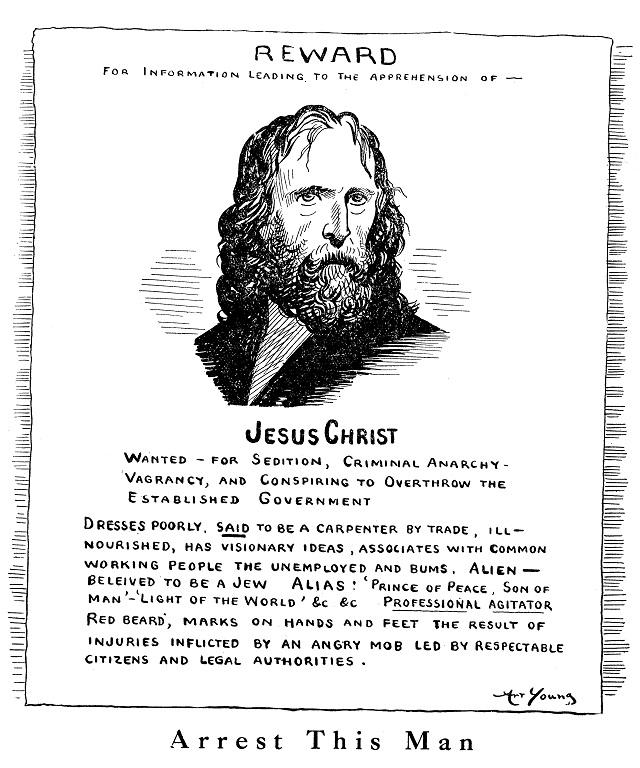

“He was of the working class and loyal to it in every drop of his hot blood to the very hour of his death,” wrote Debs, a fan of artist Art Young’s sketches depicting Jesus as a labor organizer and revolutionary, some of which were used to illustrate Debs’ published essays.

Debs’ biographer Nick Salvatore points out that comparisons to Jesus were a staple of contemporary admiration for the charismatic Debs. That was especially true after Debs’ arrest and imprisonment.

“You are wounded for our transgressions,” Unitarian minister John Haynes Holmes wrote to Debs in prison. “By your stripes we shall be healed.”

Debs’ fellow prisoners called him “Little Jesus.” Another minister, when nominating Debs for president, said that Debs’ release from his earlier imprisonment, for leading the Pullman Strike of 1894, was akin to emerging from a tomb to deliver a message of resurrection.

As Debs’ statements to the prison clerics showed, he did not shy away from the identification.

“He found a role model, oftentimes in a very literal sense, in Christ,” says Allison Duerk, director of the Debs Museum, located in Debs’ former home in Terre Haute, Indiana, and managed by a foundation co-founded by Rev. Holmes. “He called Moses a strike leader, and many times returned to the theme that he and we should always consider ourselves our brothers’ keepers.”

Salvatore says that the historic leaders of the Judeo-Christian tradition supplied the foundation for Debs’ development as a radical activist.

“In the patriarchs of the Old Testament and the angry Christ of the New, Debs found a prophetic model that legitimized his critique and demanded no apologies for frank, even harsh, pronouncements,” Salvatore wrote.

Beyond the sense of personal kinship, Debs and his comrades insisted that their cause mirrored that of the religion named for a working-class revolutionary.

“What is socialism?” Debs asked. “Merely Christianity in action.” As for capitalism, the Bible revealed its sinful nature. “Cain was the author of the competitive theory, while the cross of Jesus stands as its eternal denial.” Debs said, quoting the socialist minister and professor George Herron.

Thus, the profit motive cannot be reconciled with the core Gospels message. “We know that economic conditions determine man’s conduct toward man, and that so long as he must fight him for a job or a fortune, he cannot love his neighbor,” Debs said.

“I Hate Hypocrisy”

The embrace of Christianity seems to clash with Debs’ public and personal relationship with organized religion, which ranged from disengagement to bitter condemnation. As Jacob Dorn described in his 2003 article on Debs’ relationship with socialist Christians, neither Debs’ Protestant father nor his Catholic mother attended church, and Debs was never baptized. At age 13, a teacher gave Debs a Bible, and inscribed in it, “Read and obey.” “I never did either,” Debs boasted.

That story was more of a “cheeky quip” than a factual account, writes Debs archivist Tim Davenport, pointing out the extensive Biblical references and metaphors in Debs’ writing and speeches. But the anecdote was far from Debs’ only denunciation of the mainstream religious practices and leaders of his day.

“If I were hungry and friendless today,” he once said. “I would rather take my chances with a saloon-keeper than with the average preacher.”

In particular, Debs and his fellow socialists engaged in a multi-decade war of words with the Roman Catholic Church. To be fair, it was a fight the Church started. Priests condemned Debs and socialism from their pulpits and Catholic organizations like the Knights of Columbus distributed handbills and bought newspaper advertisements labeling socialism as atheistic and immoral.

But Debs directed his critique of Christian churches not at their faith in the Gospels, but their failure to follow them. We don’t have to wonder how Debs would reconcile his affection for Jesus’ message with the so-called prosperity Gospel embraced explicitly, and more often implicitly, by so many affluent Christians today.

“(T)he dead Christ was metamorphosed from the master revolutionist who was ignominiously slain, a martyr to his class, into the pious abstraction, the harmless theological divinity who died that John Pierpont Morgan could ‘be washed in the blood of the lamb,’” Debs wrote.

“Some called Debs a man of God and some called him a patriot, and others insisted he was neither,” Duerk says. “But with both religion and the United States, he saw their principles and potential, so he was not afraid to hold them to high standards.”

Foreshadowing Gandhi’s famously withering analysis — “I like your Christ, but not your Christianity”—Debs explained his absence from Sunday morning services. “I never darken a church door because I hate hypocrisy almost as much as I love the character and teachings of Jesus Christ. Christianity is a beautiful faith. The only trouble is that there are so pitifully few Christians in the world.”

There may have not been enough of them to his liking, but Debs did find common cause with many Christian socialists. He considered himself to be “in spiritual communion” with Social Gospel leader and Baptist minister Walter Rauschenbusch, who voted for Debs for president. Dorn chronicles Debs’ deep alliances and friendships with socialist Christians, many of whom assembled under the banner of the Christian Socialist Fellowship, which published the periodical Christian Socialist.

Debs’ comrades included Methodist minister and Berkeley, California mayor J. Stitt Wilson, Unitarian minister and Massachusetts state legislator Frederic MacCartney, and even a handful of socialist Catholic priests. Debs particularly admired Congregationalist minister and author Bouck White. White was imprisoned for interrupting a 1914 service of the Fifth Avenue Baptist Church, the home congregation of the Rockefellers, to demand a discussion of the question, “Did Jesus teach the immorality of being rich?”

White was not the only Christian socialist cleric who paid a price for his beliefs. As Dorn wrote, “There may have been more ex-ministers in the Socialist Party than ministers.” But they were certainly not alone, just as this era’s Christian socialist politicians like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, clergy and professors like Obery Hendricks, and writers like Sarah Ngu reflect a broader movement today.

Debs may have resisted the label of Christian, but Davenport and other Debs scholars suggest Debs was closer to being an extremely radical Christian socialist than a revolutionary Marxist.

He may be right. After all, there was no picture of Karl Marx on the wall of that prison cell.