A version of this article, written by our editor, was published in the March issue of Sojourners magazine.

Most Canadians have grown up never having to worry about paying a medical bill. Thanks to their country’s universal healthcare system, everyone gets the care they need, and at an overall cost far below what we pay in the U.S. It’s little wonder that 94 percent of Canadians report taking national pride in their health care system—even more than boast about hockey.

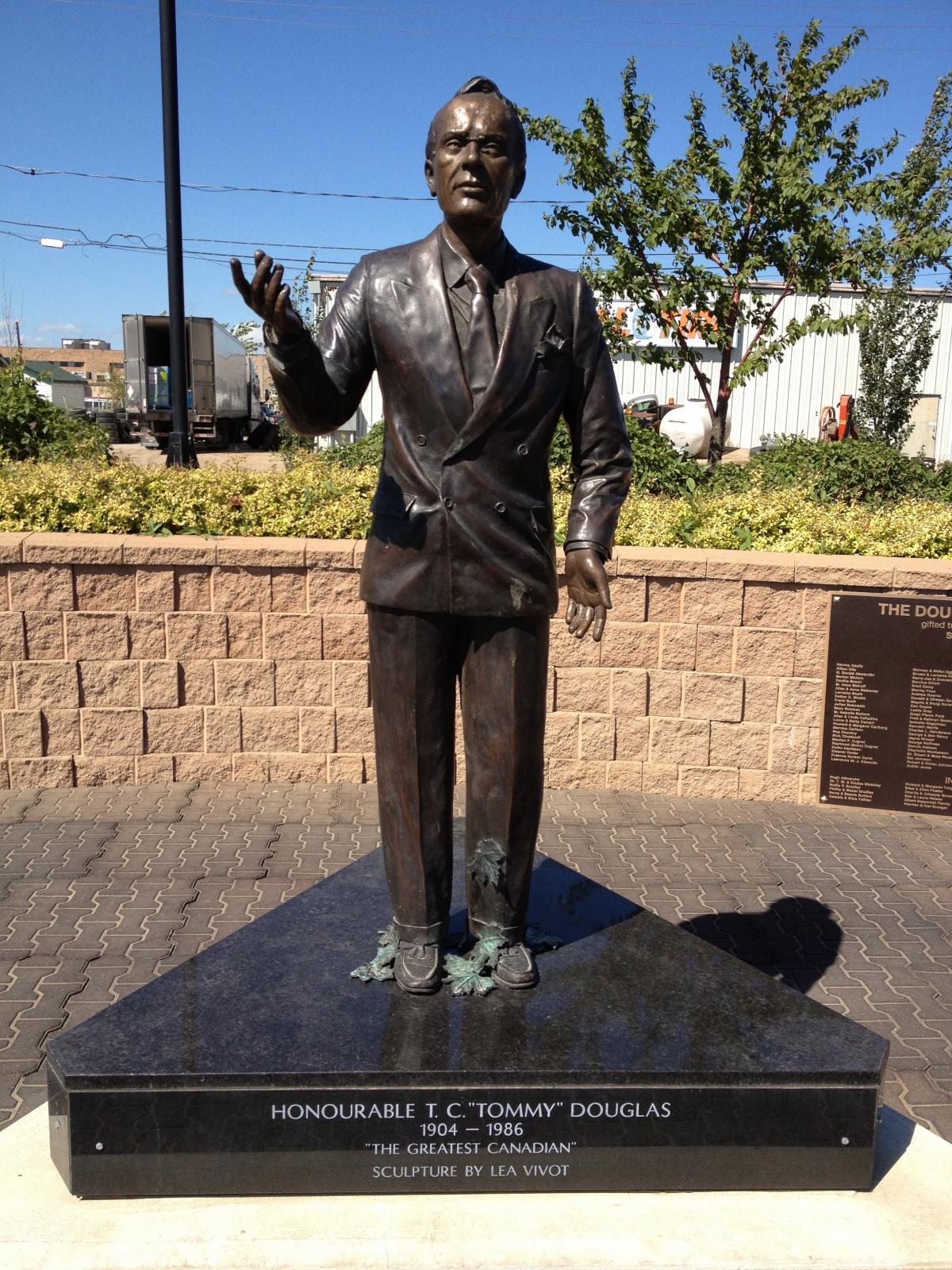

The architect of the Canadian single-payer system, Tommy Douglas, has been named “Greatest Canadian” for his achievement. Douglas rolled out the plan while serving as a five-term premier of the province of Saskatchewan. But the drive to ensure care for all did not originate in his political life. It was developed in the role that Tommy Douglas reluctantly left after he was persuaded to run for office: Baptist minister.

When Douglas became pastor at Calvary Baptist Church in Weyburn, Saskatchewan in 1930, he joined an agricultural community suffering the brutal effects of both drought and economic depression. At first, Douglas focused on coordinating intensive relief efforts. But he soon followed in the footsteps of a mentor, the former Methodist minister J.S. Woodsworth, and embraced advocacy as well.

It was not a radical detour for Douglas. He had been raised and trained in the Social Gospel tradition, which holds that it is the duty of churches and their members to push for needed political and social reforms. As Douglas put it, “You’re never going to step out of the front door into the kingdom of God. What you’re going to do is slowly and painfully change society until it has more of the values that emanate from the teachings of Jesus or from other great religious leaders.”

To Douglas, universal healthcare was an essential part of that Godly change. “How do you talk to a man about saving his soul if he’s got a toothache?” he asked. “Or worse, if he’s got a child that needs medical care and can’t get it?” So Douglas vigorously campaigned for a universal care system in Saskatchewan. After he prevailed, the success of the resulting provincial model led to the 1968 adoption of the national medicare program.

Douglas did not win that victory alone. As chronicled by the Canadian activist Joe Gunn, the faith community helped push the universal system across the finish line. “The history of church involvement in health care is a history of which Canadians can be proud, and build upon,” Gunn writes. “The churches have not been afraid to enter the political fray around health policy.”

Some faith groups, especially Catholic leadership, had initial doubts about the wisdom of a national Canadian insurance system. But an ecumenical coalition ultimately embraced the plan and then enthusiastically pushed for its adoption. Their support was critical in overcoming the fierce opposition of physician groups and the insurance industry, and cries against creeping socialism. (Does any of this sound familiar to Americans in 2019?) As one Canadian politician complained at the time, “Next you’ll be proposing grocerycare.”

But Canadians of faith insisted that universal healthcare was a moral imperative. As the Lutheran Church in America-Canada Section wrote in support of medicare, as quoted by Gunn:

"Through its emphasis on the stewardship of God’s resources for a man’s own family and for his neighbor, there is implicit the importance of individual responsibility for the health of others…In an urban industrial society individual responsibility by itself is insufficient. We are very much interdependent. Therefore, Christian concern involves a great deal more than the responsibility for one’s own health and personal concern for the sick and dying . . .When it becomes concerned with justice it ought to see health as a fundamental human right."

Of course, the struggle for human rights requires eternal vigilance. After the medicare system was adopted, the faith community in Canada was compelled to defend access to care, resist privatization, and push for expansion into prescription drug coverage and home care. As Janet Somerville, the former General Secretary of the Canadian Council of Churches wrote, people of faith took their action in the spirit of the Baptist minister-turned politician who created their program, and the generations of spiritual teaching that inspired him:

"Tommy Douglas believed that publicly funded medical care, available for everyone, has something to do with the priorities of Jesus as expressed in Matthew 25, the shared risk, the inclusive neighbourly concern, and the wide mercy that is built into the structure of a tax-supported system.

Medicare can be the Good Samaritan parable writ large, with all of us getting to be that Samaritan of whose action Jesus said, 'Go and do likewise.'"

Faith and Healthcare Notes

- New Poll Shows Suffering Due to Drug Pricing; Bipartisan Support for Reform. A new Kaiser Family Foundation poll shows that nearly one in three U.S. adults report not taking their medicines as prescribed at some point in the past year because of the cost, and a whopping 86% of Americans—including 80% of Republicans--supporting a change in the law to finally allow the federal government to negotiate with drug companies to get a lower price on medications for people with Medicare.

- Faith in Healthcare Artist-in-Residence: If you are in Wisconsin, consider visiting the “Health + the Arts” exhibition at the University of Wisconsin Eau Claire’s Ruth Foster Art Gallery from February 15 - March 13, 2019 https://www.uwec.edu/news/art-design/health-the-arts-3433/ . Faith in Healthcare artist-in-residence Katy Giebenhain has a poem included in the exhibit. Katy is the author of Sharps Cabaret (Mercer University Press).

- How Do We Pay for Medicare-for-All? Matt Breunig of the People’s Policy Project discusses in this Vox interview a proposal to fund Medicare for All in part by making payroll taxes apply more evenly to higher-wage workers than they do now. (Recall our previous Faith in Healthcare article about the PERI/UMass proposal for funding via a net-worth tax on millionaires and taxing long-term capital gains as ordinary income, among other sources.)