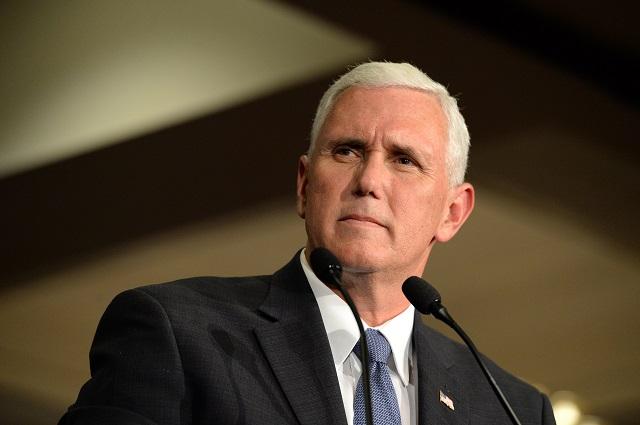

This article by our editor, co-published with the Health and Human Rights Journal, tells the story of how two ambitious Indiana politicians set out a few years ago to undercut Medicaid in their state. Now, those two Indiana politicians, then-Governor Mike Pence and his healthcare advisor Seema Verma, have ascended to the national stage. With Pence as Vice President and Verma as administrator of the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, they have vowed to make their punitive, restrictive version of Indiana Medicaid the new law of the land. But patients, activists, and attorneys from Pence’s and Verma’s home state are pushing back, in the streets and in the courts. Part two of two:

Despite the Healthy Indiana Plan blocking 70,000 eligible people from coverage, Pence and Verma claimed victory, highlighting their conservative approach to healthcare as their careers expanded beyond Indiana. In the Trump administration, they serve a boss who shares their hostility toward the ACA. Trump has called it “a big lie,” and signed an Executive Order on his first day in office calling on all federal agencies to do everything in their power to dismantle the law.

Trump’s Congressional push to repeal the ACA failed in 2017. But, outside the bright lights and resistance the administration had found in Congress, Verma began to deploy the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ substantial clout with the states to push forward an anti-ACA agenda. If the Trump administration could not repeal the ACA in one dramatic legislative act, they would take it down with a thousand cuts.

On her first day in office as administrator of CMS, Verma sent a letter to all state governors announcing her opposition to Medicaid expansion under the ACA and urging them to adopt in their states Indiana-style premiums and copayments for emergency treatment. In January, 2018, the Verma-led CMS sent another letter encouraging state Medicaid directors to impose work requirements on their enrollees.

Official Trump administration pronouncements on work requirements highlight an intent to promote the “human dignity” that comes with work. Verma herself has labeled opposition to work requirements as “a tragic example of the soft bigotry of low expectations espoused by the prior (Obama) administration.” But the numbers associated with work requirements show they would play a significant role in undercutting the ACA. The first Medicaid work requirement that Verma’s CMS approved was in Kentucky, where administrators estimated the plan would remove 100,000 people from the rolls. Sara Rosenbaum, former chair of the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, said the aim of the state’s proposal was clear: “It’s purpose is to thin the ranks.”

A federal judge enjoined Kentucky’s plans before they could take effect. But Arkansas’ CMS-approved work requirement caused 18,000 people to be kicked off Medicaid within the first nine months of its rollout, before it too was halted by court order. In March of this year, President Trump’s 2020 budget proposed applying Medicaid work requirements nationally, calculating they would reduce Medicaid costs by $130 billion over a decade.

When Work Requirements Undermine Work

Work requirements may effectively thin the Medicaid ranks and save billions of dollars, but they usually do a poor job of actually encouraging work. Many current Medicaid enrollees already have jobs. But research by the Kaiser Family Foundation shows that nearly half of those who work part-time cannot work more hours due to family or other obligations, or they are unable to find more work in communities where available jobs are often tied to inconsistent hours and low pay. Verma’s agency has blocked states from using Medicaid funds to create programs to provide work supports like training, childcare, and transportation.

Others on Medicaid are living with significant disabilities. In theory, they should qualify for exemptions from work requirements. But more than half of those disabled persons have not yet received official confirmation from the Social Security Administration of their disabled status. As a result, they are likely to struggle to obtain that exemption. So too with the millions of others on Medicaid who are caregivers for elderly or disabled family members.

For those on Medicaid who can work, the requirements often create a barrier to the purported goal of encouraging employment. People with healthcare are more likely to get a job and keep it, because they can avoid the trap of untreated conditions that mushroom into crises that require extensive care and time off work. In striking down Arkansas’ work requirements, U.S. District Court Judge James Boasberg began his ruling by telling the story of Adrian McGonigal, whose job at an Arkansas food service company did not provide health insurance. For four years, McGonigal was able to get his prescriptions filled and go to the doctor, thanks to Arkansas' Medicaid program. But McGonigal struggled with the state’s reporting mandates. One day, he went to refill his prescriptions and was presented with a bill for $800. The state had cut him off. McGonigal could not afford to pay for the medicine, and he fell ill and had to miss several days of work. He lost his job.

Push-Back from Indiana

Pence’s former Lieutenant Governor Eric Holcomb, who succeeded Pence as governor, wasted no time in taking up Verma’s CMS on its invitation to impose Medicaid work requirements. Holcomb proposed, and CMS quickly approved, sweeping new work requirement rules layered on top of the state’s premium and other requirements. (Verma recused herself from reviewing Indiana’s proposal.) Indiana Medicaid enrollees deemed able to work are now required to be employed or engage in work-related activity each week, and to report their hours. If they do not meet these requirements their health coverage will be suspended beginning January of 2020.

An actuarial firm working for the state estimated that the new work requirement will cause more than 24,000 persons to lose their Medicaid coverage each year. (Another CMS-approved Indiana penalty, a lockout of Medicaid enrollees who do not complete a redetermination process on time, could remove as many as 18,000 more people each year. When CMS issued its approval of Indiana’s request to impose work requirements, it did not mention the state’s projection that 24,000 people would lose their coverage. The state’s current director of its Family and Social Services Administration, the agency tasked with overseeing the work requirement also avoids mentioning the projected losses, instead telling media and lawmakers that the goal is for no one to lose coverage.

A coalition of Indiana advocates, including state lawmakers, urban faith organizations, and a rural community action group, are pushing back. In a series of protests and petitions, they are pressing Holcomb to withdraw his work requirements plan. And last week, in a new lawsuit filed in the U.S. District Court in Washington, D.C., Cree and other Indiana residents attacked the Trump-Pence-Verma plan at its Indiana roots. Represented by the National Health Law Program and Indiana Legal Services, they are asking that the Healthy Indiana Plan’s premiums, lockouts, and work requirements be struck down for violating the constitution and federal statutes.

It is the fourth lawsuit challenging states’ CMS-approved work requirements on Medicaid enrollees, and the other three suits have all succeeded in stopping the waivers in Kentucky, Arkansas, and New Hampshire. But this is the first to strike a blow directly at the Pence-Verma brainchild that serves as the Trump template for undermining the ACA.

The lawsuit argues that the Indiana plan, and the national Trump agenda it helped create, is a blatant effort to undermine the Medicaid Act, duly passed by Congress and signed into law. This would be a violation of Article II, Section 3 of the U.S. Constitution, which requires the executive branch to “take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed.”

The lawsuit’s initiating Complaint is 55 pages long, but its first paragraph tells the tale: “The Executive Branch has instead effectively rewritten the statute, ignoring Congressional restrictions, overturning a half-century of administrative practice, and threatening irreparable harm to the health and welfare of the poorest and most vulnerable in our country.” Those poor and vulnerable Americans are now striking back, and they are doing so from Mike Pence’s home state.

Faith and Healthcare Notes

Will the Trump-Pence Medicaid Work Requirements Survive the Court Challenges? Last week, a three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals heard oral arguments on appeals from rulings that struck down work requirements planned for Kentucky and Arkansas. Multiple reports from the hearing suggest the judges were leaning toward the view that work requirements don’t meet the legal requirement that changes to Medicaid support its core objective of providing health coverage.

Medicaid Red Tape Not Only Blocks Healthcare, It Costs Taxpayers. A new U.S. Government Accountability Office report underscores that millions are being spent on the administrative costs of adding on work requirements, but the Trump administration is not being upfront about those costs: “CMS has acknowledged that demonstrations, including those with work requirements, may increase Medicaid administrative costs—and therefore overall Medicaid spending. Yet, CMS is not factoring these costs into its approval decisions, which is counter to the agency’s goals of transparency and budget neutrality.”

The “Skin in the Game” Premise for the Trump-Pence Plans Debunked--Again. A new report from the Los Angeles Times is the latest to show that the lack of transparency in healthcare costs, emergency needs, and limited choices and understanding of options continue to undermine the fantasy of Americans being empowered shoppers for healthcare. “This idea that we were going to give patients ‘skin in the game’ and a few shopping tools and this was going to address the broad problems in our healthcare system was poorly conceived,” Lynn Quincy, former healthcare advocate at Consumer Reports now at Altarum, a nonprofit research and consulting firm, told the Times.